Embracing a New Ethos in Business

Management as a calling

A literal and figurative tipping point in Gabriel Correa’s life came five years ago during Hurricane Maria when the deadly, destructive storm leveled the trees in the backyard of his family’s home in Puerto Rico.

business acumen toward helping rebuild

Puerto Rico. (Image credit: Jeff Karoub.)

There was an area (nearby) that I didn’t know existed, and I just saw houses without roofs — it was literally like a curtain opened,” said Correa, then a junior in high school and now an undergrad at the Ross School of Business.

Correa, BBA ’23, surveyed the destruction and realized how fortunate he was. It was then he decided to pursue a business education. There had to be a career that would help him improve lives and the economy in Puerto Rico.

His desire led him to U-M and in September, to the University’s Biological Station in Northern Michigan, for the unique retreat, “Management as a Calling.” Correa joined nearly 40 Ross undergraduate and graduate students at Lake Douglas in Pellston, Mich., for the debut program.

Their host was Andy Hoffman, the Holcim (U.S.), Inc. Professor of Sustainable Enterprise. He holds a joint appointment at Michigan Ross and the School for the Environment and Sustainability. His recent book, Management as a Calling (Stanford Business Books, 2021.), inspired the course. It also inspired Correa.

“It’s all about looking for how you can link your passion to your calling within business; I thought it was something I needed,” the BBA student said. “I have a lot of friends who have pursued careers in banking — which I definitely respect — but I felt the way to fulfill myself is to do something beyond that of business as usual.”

Beyond business as usual

Above and beyond

Though students’ backgrounds and ambitions varied, the participants all shared a common objective: Look beyond bottom lines and explore professions that could lead commerce and serve society.

She recalled looking around the plant floor during a product trial.

“The amount of food waste I was standing next to was more than I could swallow from an impact perspective — hundreds and thousands of pounds of food that’s no longer needed,” she said.

The incident certainly caused some cognitive dissonance: Bravard says she was “doing everything that you call successful as a young scientist in a large organization,” yet, she adds, “I wasn’t thinking about all the people impacted by the new products and supply chain.

“The dissonance, I suppose, was big enough in my personal journey to ask: ‘Am I fulfilled by what I am doing?'”

The retreat offered “a respite from the traditional MBA rhythms,” Bravard said, and offered her a chance to reflect and “write myself a little manifesto” for guidance. One of her favorite places to read, write, and reflect at the Biological Station was sitting cross-legged on an otherwise empty volleyball court.

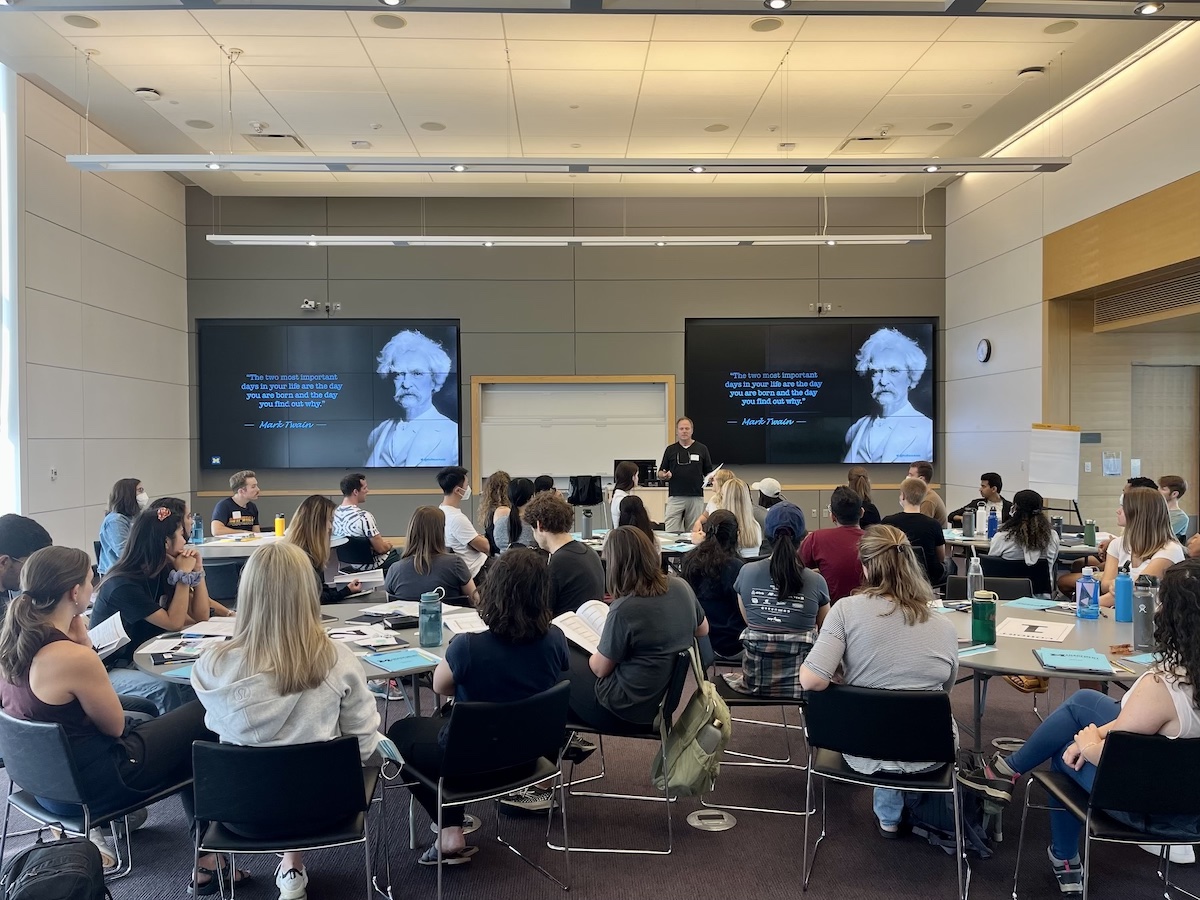

Twain’s world

with inspiring quotes. (Image credit: Jeff Karoub.)

Hoffman kicked off the weekend with a welcome session at Ross. On the screen behind him was a quote from Mark Twain that would serve as an organizing principle for the retreat: “The two most important days in your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why.”

Hoffman also displayed inspiring words of wisdom from sages as diverse as the Buddha, Oprah Winfrey, Socrates, and Eleanor Roosevelt. Even the late actress/author Carrie Fisher got a shoutout with this quote: “There is no point at which you can say, ‘Well, I’m successful now, I might as well take a nap.”

The Fisher quote is an important sequel to Twain’s, Hoffman said. He praised the students for “choosing to find that ‘second day’ — most people don’t choose to do this.” Still, he advised, “finding out the why” is a lifelong pursuit.

“This doesn’t end this weekend,” he said. “Plan for some unfinished business; plan for a lot of unfinished business. We want to start you on the process of thinking this through and make this a part of your life going forward.”

Appropriately, the retreat itself is only the first step. Students will attend lectures, a follow-up retreat in the spring and a virtual meeting one year after that.

Unfinished business

Station in Pellston, Mich. (Image credit: Jeremy Marble.)

“Management as a Calling” was made financially possible by a grant from The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations. Hoffman said the idea manifested when he received a call from a foundation official seeking recommendations to direct funding within the sustainability space.

After a long conversation, he said the official asked what Hoffman was working on. He mentioned the book and the ideas behind it.

“I explained it all, and he said, ‘If you were to lead a program, what would you do?’ I said, ‘Well, I’d do this,'” Hoffman told the students. “So he said, ‘Pitch it, and I think we might give.’ We went back and forth until last March, when they called me and said, ‘Here’s your funding. Go do it.'”

Hoffman launched the program with significant effort from five teaching assistants — some graduate students themselves, others now out of school finding their way in the working world —who helped animate the principles from his book and related courses.

The team wanted to present material that compensated for deficiencies at the core elements of business education.

“Is it really about ego gratification and profit maximization, or is it about something bigger, a purpose?” Hoffman said. “If that piece isn’t there, you need to bring it in. I’m not here to knock down business education; I’m here to help you to see its strengths, its weaknesses, where it serves you where it doesn’t and how you augment it to make it what you need it to be.”

or acquaintances discovered quite a bit about

each other during the intense weekend.

(Image credit: Jeff Karoub.)

Although the retreat had a “what’s said here, stays here” dictum, Hoffman encouraged students to share elements of their weekend experience with others. It’s an actual condition of the grant to spread the message behind the “Management as a Calling” experience and explain the broader value the program could offer other schools and society at large.

“It’s OK to be uncomfortable,” Hoffman told the students. “In fact, you will be uncomfortable sometimes if we’re doing it right.”

To be sure, comfort levels ebbed and flowed during more intimate, small-group settings, where participants shared passages from their “life aspiration statements.” Tears and laughter were shared among strangers, acquaintances, and, ultimately, friends.

Some participants spoke of childhood trauma or the pain they saw in the world around them. They talked about their mental health struggles or those of loved ones. A few shared stories of being immigrants or the children of them, including the challenge of navigating two worlds and not being fully understood or acknowledged. One student said he’s trying to figure out how to merge his outsized passions for community service with a career.

Life in the dash lane

Nikita Mihalkin, BBA ’23, came to the United States from Ukraine nearly a decade ago when he was 11.

Recognizing the opportunities in his new home, he said his parents and others pushed him to “have a great career and make a lot of money.” He felt fortunate to be accepted as a business major at Michigan Ross, but he also noticed a clear emphasis on pursuing lucrative careers in finance or consulting.

Hoffman’s book struck a chord with him, particularly the notion that “happiness doesn’t stem simply from having lots of money.” That experience led Mihalkin to apply for the program to understand how he could do well for himself and good for the world.

Mihalkin thought about the struggles of his family and those still in Ukraine, especially since Russia’s forced annexation of territory eight years ago, full-scale invasion earlier this year, and ongoing, brutal war. He believes in “the American dream,” he said, but making it all about chasing wealth would be a disservice to suffering friends, family and others.

“I always had a sense there was a lot of luck involved (in my journey). It can’t be coincidence,” he said. “I feel a debt or duty to perform good deeds in service to society.”

At one point during the weekend, each student created a document encompassing their past, present and imagined future. Hoffman directed them to craft a personal obituary, which “should be done as if written for the local newspaper by your best friend who knows the real you in addition to your accomplishments.”

Tom Krautler and Allison Winstel, two of the program’s teaching assistants, were enthused about the weighty task.

Krautler, MBA/MS ’23, a third-year dual degree candidate at Ross and the School of Environment and Sustainability, said he wrote his obit as part of a capstone class during his last undergraduate year. “The assignment caused everything to hit all at once,” he said.

“Think about that,” Krautler told the participants, who are in their final year of study, whether fourth-year undergraduates, second-year graduate students or in one-year master’s programs. “We don’t know how much we have right here. What do you want to be known for? What do you want people to think about you? How do you want to be seen? This experience was really powerful for me to think about.”

Winstel, MBA/MPP ’22, shared excerpts from “The Dash,” a poem by Linda Ellis. The dash specifically refers to the space between the date someone is born and the date someone dies.

“So when the eulogy is being read … would you be proud of the things that they say about how you lived your dash?” Winstel read.

“That for me has been how I think about ‘What do I want the years to look like?'” said Winstel, who now works as chief of staff for mHUB, a hardtech and manufacturing innovation center. Hardtech combines hardware and software to solve a problem for a particular industry.

“I wanted people to reflect on my life and remember me as someone who showed up for them, who brought energy and optimism into life,” she said.

Everyone can have a purpose, but not everyone looks for one. You have chosen to look for one, which is the key that makes all the difference in a meaningful life.

Winstel said taking inventory of her life and writing the obituary made her realize that she’s “not a very goal-oriented person,” but rather someone who formulates “a vision of who I want to be … and then I head in that direction.”

“I have been on my own journey to find my calling for many years now,” she said. “My ‘aha moment’ was when I realized I had to let go of having the perfect 5- or 10-year plan and instead focus on the journey. I noticed that what I thought I wanted to do was almost always wrong, but when I leaned into the work that energized me, I always went in the right direction.”

Deep in nature

business students the space to “push against

the tide and bring about a new ethos in

business.” (Image credit: Jeff Karoub.)

To reflect and write, some participants chose picnic tables or a patch of ground overlooking Douglas Lake, where U-M scientists have conducted research for more than a century. One student waded waist-deep in the water before setting upon a floating dock to put pen to paper.

As expected, most students didn’t come away from the retreat with a detailed map for their lives but rather a more finely calibrated compass.

For Bravard, the retreat helped her reflect on the career she left for grad school but remains close to her heart: “What do I love about food science? What don’t I love? How could I use my degree to make the world a better place, potentially in a different type of role?”

The retreat’s exercises confirmed Mihalkin’s highest priority — “creating impact and being good at the work I do,” rather than simply making money. He’s still exploring the high-tech entrepreneurial space but in a strategic, behind-the-scenes role where he could “help people around me.”

For Correa, “Management as a Calling” didn’t answer all of his questions but set “a really robust path toward answering them.” It was unexpectedly enlightening to be deep in nature with fellow business students engaged in such personal pursuits, he said.

“Everyone here has brought in so many perspectives that I truly did not take into account before,” Correa said. “I can definitely say it has enhanced me in a way and rectified my drive to pursue that calling of helping out Puerto Rico.”

Detour of duty

shared with students his own journey to discover “management

as a calling.” (Image credit: Jeff Karoub.)

Even Hoffman said he derived value from the inaugural retreat: At 60, he’s trying to discern his “next act.”

He told the group he opted to pursue chemical engineering as an undergraduate for “the worst possible reason” — it was the toughest major on campus, and he was “a young turk” out to prove himself. During his studies, the world learned about Love Canal in New York, the site of one of the nation’s worst environmental disasters. This spurred the creation of the federal Superfund program that oversees the cleanup of hazardous waste sites.

The environmental catastrophe also spurred and shocked Hoffman, changing his path from a career to a calling. He was driven to ensure that such a disaster didn’t happen again. His first job was with the Environmental Protection Agency. Trouble was, he loved the mission but hated the work. Public policy seemed like a better path, so he applied to grad school.

Hoffman was accepted at Harvard and the University of California, Berkeley, but “froze” because neither felt right. Meanwhile, he had been helping a friend build a deck and kept getting carpentry jobs. One of his projects was at the home of the late Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric. That led to supervisor roles on several more “extremely huge homes for extremely wealthy people.”

embrace a moral compass. (Image credit: Jeff Karoub.)

As much as he loved the work, Hoffman aspired to higher goals. Still, the experience served a purpose. The detour into construction represented the first time Hoffman had taken control of his own life and helped him see how he could build on and share his know-how and passion for protecting the environment. He earned his master’s and doctoral degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and became an educator.

“You can find your way in the strangest of ways,” he said.

Hoffman, whose 18 books include a memoir about that experience as a builder’s apprentice, said the real value of the weekend for participants and facilitators was to think deeply about their journeys and what they want to find on them — whether negotiating a path, living a dash or trying to keep hold of the wheel on a twisty road.

“We want you to examine your values, your purpose. Yours alone. You have to find it,” he said. “Everyone can have a purpose, but not everyone looks for one. You have chosen to look for one, which is the key that makes all the difference in a meaningful life.”

(Lead image of students on the beach at Lake Douglas by Jeremy Marble.)