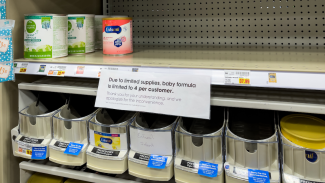

What You Need to Know About the Defense Production Act – The 1950s Law Biden Invoked to Try to End the Baby Formula Shortage

U.S. President Joe Biden on May 18, 2022, announced he is invoking the Defense Production Act to help end the shortage of baby formula stressing out parents nationwide.

He said he will direct suppliers of baby formula ingredients to prioritize delivery to formula manufacturers and control their distribution as necessary.

You might well wonder what babies going without formula has to do with defense production, which calls to mind big warships and weapons systems. While using the Defense Production Act to force companies to make baby formula would certainly be a novel use of the act, it would hardly be the first time the postwar law has been used beyond its originally intended purpose to support national defense.

And in fact, the law is used a lot more frequently than you might think. But as a business professor who studies strategies to maximize efficient allocation of resources, I believe when presidents invoke the act it’s often more about political theater – showing the public you’re doing something – than addressing the problem in the most effective way.

Sweeping authority

The Defense Production Act was passed in 1950 and modeled on the War Powers acts of 1941 and 1942.

The War Powers acts gave the president sweeping authority to control domestic manufacturing. For example, it helped the U.S. increase production of warplanes from 2,500 a year to over 300,000 by the end of the war.

In 1950, America faced war in Korea, and Congress feared that growing postwar demand for consumer goods would crowd out defense production needed to face China and the Soviet Union, which both backed North Korea in the conflict. There were also concerns about inflation during that postwar period.

The Defense Production Act gave the president – who later delegated this authority to Cabinet officials like the secretary of defense – broad powers to force manufacturers to make goods and supply services to support the national defense, as well as to set wages and prices and even ration consumer goods.

“We cannot get all the military supplies we need now from expanded production alone,” President Harry Truman told Americans in a radio address after signing the act into law. “This expansion cannot take place fast enough. Therefore, to the extent necessary, workers and plants will have to stop making some civilian goods and begin turning out military equipment.”

The original law focused on “shaping U.S. military preparedness and capabilities,” which limited the scope of the president’s authority.

Routinely invoked

Although the Defense Production Act makes news only when the president dramatically invokes it, the government uses the law – or just the threat of using it – routinely to force private companies to prioritize government orders. The Department of Defense, for example, uses it to make an estimated 300,000 contracts with private companies a year.

Congress has to reauthorize the act every several years and has amended it frequently to expand or limit its scope. Over time, this has significantly broadened the definition of national defense to include supporting “domestic preparedness, response, and recovery from hazards, terrorist attacks, and other national emergencies.”

The Department of Homeland Security invoked it about 400 times in 2019, mostly to help prepare for and respond to hurricanes and other natural disasters, such as by providing resources to house and feed survivors. And Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, for example, both used it to divert electricity and natural gas to California during the 2000-2001 energy crisis.

The act has also been used extensively during the COVID-19 pandemic. President Donald Trump used it to prioritize the allocation of medical resources, prevent hoarding of personal protective equipment, and require General Motors to build ventilators. He also ordered beef, pork, and poultry processing facilities to stay open during the lockdowns to ensure a supply of protein for the American population.

Biden, for his part, has also already used the act a number of times, mainly to fight the pandemic. For example, in March 2021, he invoked it to speed up vaccine production by ensuring extra facilities were up to snuff, as well as to expedite the production of critical materials, equipment, machinery, and supplies. In March 2022, he issued a directive to increase the supply of materials for large-capacity batteries that are used mainly in civilian electric vehicles.

Biden’s use of the Defense Production Act to address the baby formula problem illustrates a limitation of it. It can be used to set priorities for ingredients and manufacturing capacity, but it’s not a magic wand. A president can’t by decree make capacity that doesn’t exist instantly appear. And it isn’t clear how much it will do to quickly end the formula shortage – given the main problem is manufacturing issues that closed production at a key plant, not just a shortage of ingredients.

The act is widely used and has been widely useful, but it is no substitute for advance planning and preparedness.