A Biden Business Agenda: Boosting Employment While Fighting a Pandemic

This is the fifth in a series of articles asking Michigan Ross professors what they hope to see from the incoming Biden administration on specific business topics. In this post, Professor of Business Economics and Public Policy Jagadeesh Sivadasan addresses employment and wages.

What immediate, short-term actions should the Biden administration take to counteract the unemployment and strain on small businesses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic?

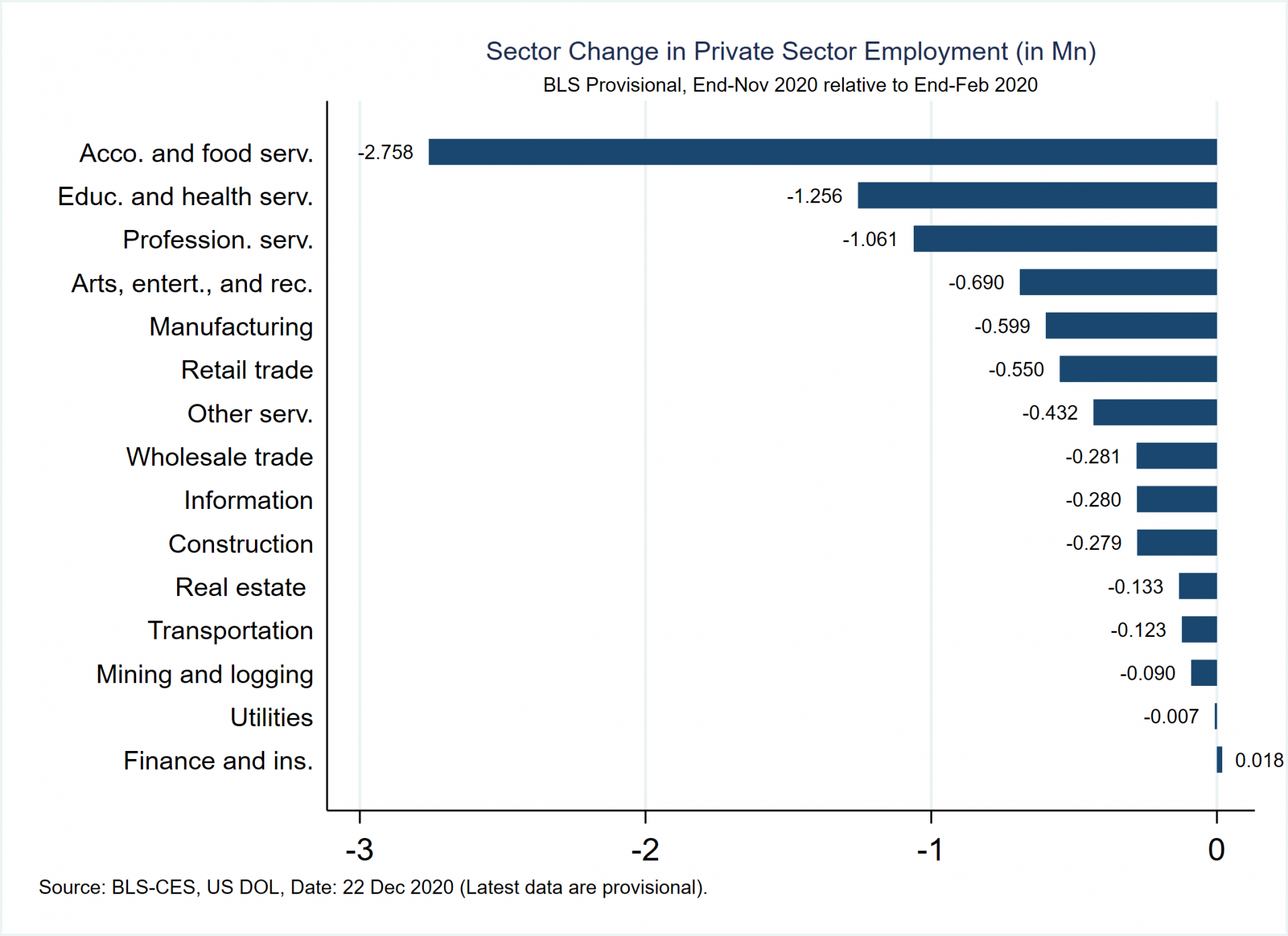

Sivadasan: As economists noted at the very beginning of the pandemic, the strength of the economic recovery depends crucially on the extent and depth of the pandemic. The critical importance of getting the pandemic under control is illustrated by the nature of the current unemployment crisis — the biggest job losses have been in the accommodation and food services (i.e., hotels and restaurants) sector, where both government social distancing mandates and changes in consumer behavior have led to plummeting demand.

Sivadasan: As economists noted at the very beginning of the pandemic, the strength of the economic recovery depends crucially on the extent and depth of the pandemic. The critical importance of getting the pandemic under control is illustrated by the nature of the current unemployment crisis — the biggest job losses have been in the accommodation and food services (i.e., hotels and restaurants) sector, where both government social distancing mandates and changes in consumer behavior have led to plummeting demand.

The additional fiscal relief package that was recently passed by Congress should help alleviate distress for workers and employers. Extension of supplemental unemployment benefits for 11 weeks, and the provision of $600 of direct payments to adults and children, will not only help the direct recipients, but will be vital to keep consumer demand strong. Also, the extension of the Paycheck Protection Program will help sustain small and medium businesses.

There has been significant strain on the resources for state and local governments, and vaccination efforts will impose additional costs. The Biden administration will need to work with Congress to provide federal assistance to states, in order to avoid layoffs in state government, which could add to the job losses in other sectors.

Ultimately, a coordinated and well-scaled effort that achieves rapid vaccination of a large fraction of the population would be the best strategy for a speedy economic recovery. A significant issue is that a part of the U.S. population has skepticism about the vaccines. A crucial challenge for the Biden administration is communicating the safety of the vaccines to the skeptical Americans in a credible way.

What additional, longer-term moves should the new administration make to help ensure that employment stays strong in the future?

Sivadasan: To sustain recovery in the medium term, the administration could structure assistance (e.g., subsidized loans or grants) to new entrants (the Biden transition site mentions a “Main street comeback package,” and the Biden-Harris platform included funding for new and small businesses). Another idea could be wage subsidies for startups — especially in the most affected restaurant, accommodation, and travel sectors — which have been effective in boosting employment in other contexts.

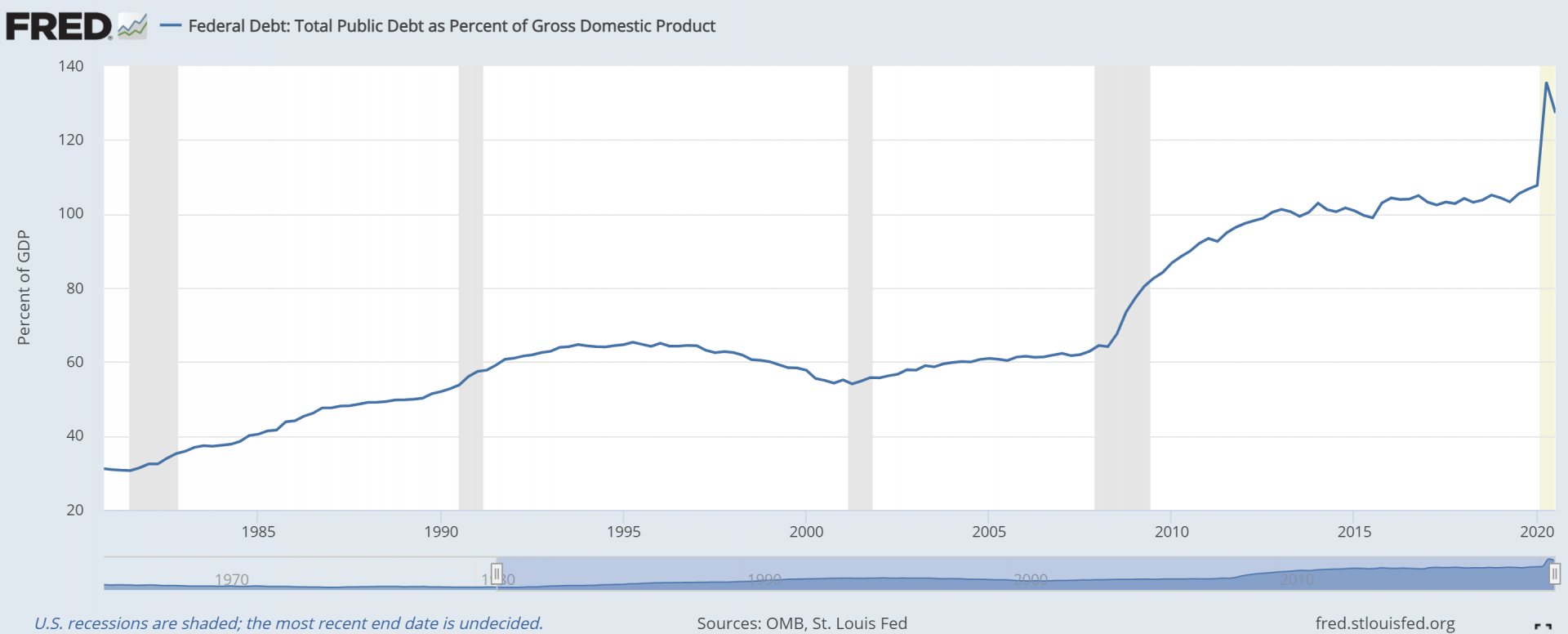

Other longer-term priorities for the Biden administration include expanding healthcare access, forgiving student loans, and building infrastructure for a clean energy economy. Unfortunately, the new administration may be constrained by the fact that the pandemic has required significant expenditure by the government, which has steeply increased public debt to the highest levels in decades.

While some economists argue that there is significant room for further spending, there may be strong political resistance to this, as evidenced by the difficult negotiations over the latest pandemic relief bill. A crucial indicator would be inflation and interest rates; if these continue to remain low, the administration may eventually be able to obtain support for spending on other longer-term priorities.

Should the minimum wage be increased? If so, to what level?

Sivadasan: A July 2019 Congressional Budget Office report nicely summarizes the pros and cons of raising the federal minimum wage from the current level of $7.25/hour, to $10, $12 or $15 per hour by 2025. The Biden-Harris platform included support for an increase to $15 per hour. Per the CBO analysis, such a change would boost the earnings of over 27 million workers (including for 17 million workers who would otherwise earn less than the minimum wage), and raise about 1.3 million people above the poverty threshold.

Of course, the main concern is whether higher wages would force firms to cut back on employment; the CBO estimated a 66% chance of job losses in the range of 0-3.7 million. A more moderate increase to $12 would entail a much lower potential job loss of 500,000, but would only impact a total of 11 million workers, and lift just 400,000 people above the poverty threshold. (The numbers for impact of the federal minimum wage are likely lower now, as Florida voters just approved a gradual increase in the state’s minimum wage to $15 by 2026. )

Most states already have a minimum wage above the federal minimum wage (and in many cases above $10 or planned to be above $10 by 2025). Not surprisingly, the CBO estimates that an increase in federal minimum wage to $10 would have negligible effect on wages and poverty, and hence entail almost zero job losses.

One moderate approach could be to target a lower increase in the federal minimum wage, and index it to inflation (as is the norm in many states), so that inflation does not erode the relative value of the minimum wage. Another idea could be to provide help to employers in mitigating extra costs imposed by the minimum wage, for example through a (temporary) wage subsidy program tailored to assist only those few employers genuinely impacted by the increase.

How likely is the adoption of Biden’s workers’ rights plan? What effect would that have?

Sivadasan: Given the close divide in the Congress, passing sweeping new legislation that achieves all of the goals of Biden’s workers’ rights plan seems unlikely in the short term.

However, a number of objectives set forth the workers’ rights plan could be at least partially accomplished through executive action by the Biden administration, as pointed out by some commentators. These include strengthening bargaining rights (by reversing a number of Trump administration's executive orders); changes in regulations and added OSHA personnel to improve worker safety; changes in regulations to improve rights for gig workers; and expanding mandated overtime to workers.

The argument for these pro-labor reforms is that wages for lower-earning workers have grown much slower than for higher earners for several decades, and the share of value added that goes to workers has been declining for several years. The resistance from businesses to many of the proposed changes relate to increased labor costs, which in the short term may lead to lower profits. But there is arguably also a threat of lower labor demand, which reduces the number of jobs and hence could hurt workers as well. The weakness of the labor market for lower wage workers who have suffered the most from the pandemic complicates this discussion; the case for pushing ahead with the workers’ rights platform may be stronger once the unemployment levels for lower wage workers have declined.