Business Begins at Michigan

The beginnings of business education at the University of Michigan date back to the late 1800s, when business was often considered a basic trade and a far cry from true professions like medicine, law, or engineering. We can thank risk-takers and innovators like U-M President James Angell and economics professor Henry Carter Adams for seeing the promise of studying business theory. They set U-M on the path of applying scientific principles to business practices that changed the university and worldwide communities for generations to come.

While serving as U-M’s president from 1871-1909, Angell led massive population growth among students (enrollment grew from 1,100 to 5,000) and faculty (35 to 250), and expanded educational offerings. He favored new ways of thinking and scientific investigation, which paved the way for the School of Dentistry, School of Pharmacy, School of Music, Nursing School, and School of Architecture & Urban Planning during his tenure. U-M’s mainstay, the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, also grew as the 20th century approached. Angell promoted Adams, a virtuous, young professor, to chair the newly-created economics department. Similar to Angell’s belief in research, Adams thought that economic behavior could be studied and regulated to improve society as a whole.

Business as a Science, Not Just a Trade

While Adams set out to “supply business talent of a superior order,” he had to contend with naysayers. He noted that “there is no typewriting, no stenography, no bookkeeping, no play at banking… those things are left where they belong in the commercial courses of the high schools and business colleges.” Adams believed he could help unlock America’s commercial potential through the study of business theory and administration. The first “business” classes were available in Fall 1900, and soon, the catalog of courses included accounting, finance, wholesale and retail trade, statistics, railway organization and operation, and investment. Additionally, a marketing class was considered the first of its kind nationwide.

Adams’ economics courses gained traction with students throughout the first two decades of the 1900s. Enrollment in the Department of Economics grew from 950 in 1914 to nearly 1,400 in 1919. Outside the classroom, the public started to view business administration as being on par with other elite professional pursuits. Adams passed away in 1921 while he was still chair of the Department of Economics.

President Burton Believes in Business

In 1920, U-M and the rest of the nation were rebounding from the throws of World War I. U-M’s enrollment was on the rise, surpassing 10,000 for the first time in 1920-21, and Marion Leroy Burton was in his first year as U-M’s president. Burton saw the promise of Adams’ profound work and ventured east for another visionary who could lead U-M forward, Edmund Ezra Day.

President Burton was incredibly productive in the five short years he spent as U-M’s president (he passed away in 1925 while in office). His “comprehensive building program” ushered in many of the campus buildings we still see today surrounding the Diag. One of Burton’s most impactful hires was Day, who demanded a hefty salary to leave Harvard University. Day possessed a PhD from Harvard, taught at Dartmouth College’s business school, and was the Chief Statistician of the Central Bureau of Planning and Statistics in Washington during World War I.

Day took over as chair of the Department of Economics upon his arrival in 1923, however, he and Burton were intent on quickly establishing a formal business school. At the Dec. 21, 1923, Board of Regents meeting, Day successfully presented his plan for the School of Business Administration, which was scheduled to operate independently of the College of LS&A starting in the 1924-25 academic year. The degree of Master of Business Administration would be awarded upon successful completion of two years of study. Admission required three years of work in LS&A, or of equivalent work.

Day, like his predecessor Carter, was focused on shaping business leaders, not followers, who could build relationships between business and community. His focus was to use research and analysis to guide the curriculum, telling the Detroit News, “We do not plan to make expert technicians. Ours is the task of making business scientists.”

Day’s Profound Predictions

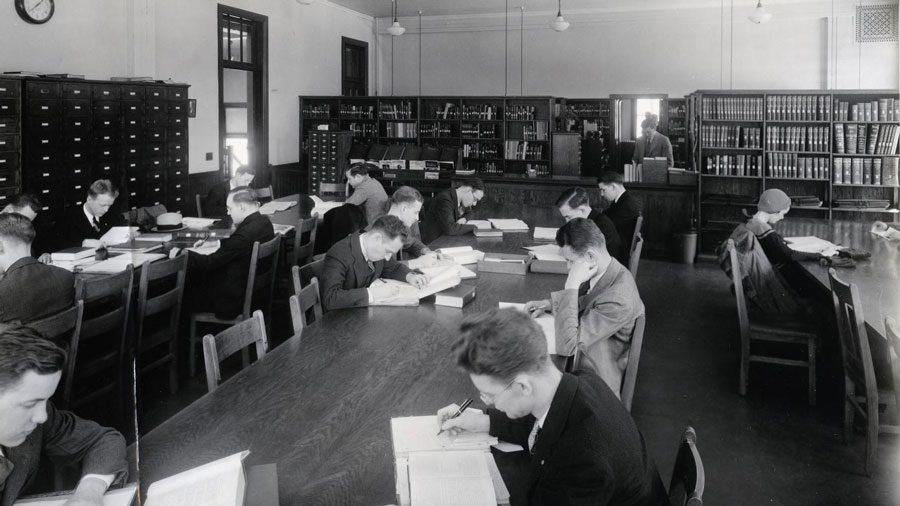

The U-M School of Business Administration opened its doors to students in September 1924. The first home of the school was Tappan Hall, just west of the U-M president’s house on South University. There were 22 MBA students, 19 of whom completed the work for the year, and 14 faculty members.

Even in its inaugural year, Dean Day welcomed and recognized the importance of non-business school students. In his 1924-25 report to President Burton, Day had the foresight to state: “One hundred and thirty-eight students from other schools and colleges of the University elected courses in the School of Business Administration. One hundred and twenty-one of these students came from the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. The School of Business Administration, in giving instruction to such students, renders an important service to the university. The extent of this service is not fully shown by the number of outside students who have received instruction in the school.

“Rapid development of the organization is necessary if it is to serve satisfactorily the student body, which it should attract in the immediate future. A number of additional faculty appointments must be made to cover satisfactorily the more important fields of specialization in the second-year work of the school. A separate library should be brought together and developed as rapidly as possible. A Bureau of Business Research should be established (this was accomplished in 1925) to bring the school into effective contact with outside business and to enrich the professional courses in its curriculum. Additional rooms for classes must be provided in the immediate future, and a separate building constructed as soon as the normal enrollment of the school can be estimated. All of these needs must be met promptly if the school is to take its place among the ranking professional schools of Business Administration in this country.”

Ninety-nine years later, it’s safe to say that Dean Day’s year one remarks were almost perfectly targeted in setting the school up for decades and now a century of successfully training outstanding business people.